REVIEW: Tan Dun Brings Nature's Secrets to The Orchestra Now

November 12, 2018

By Brian Taylor

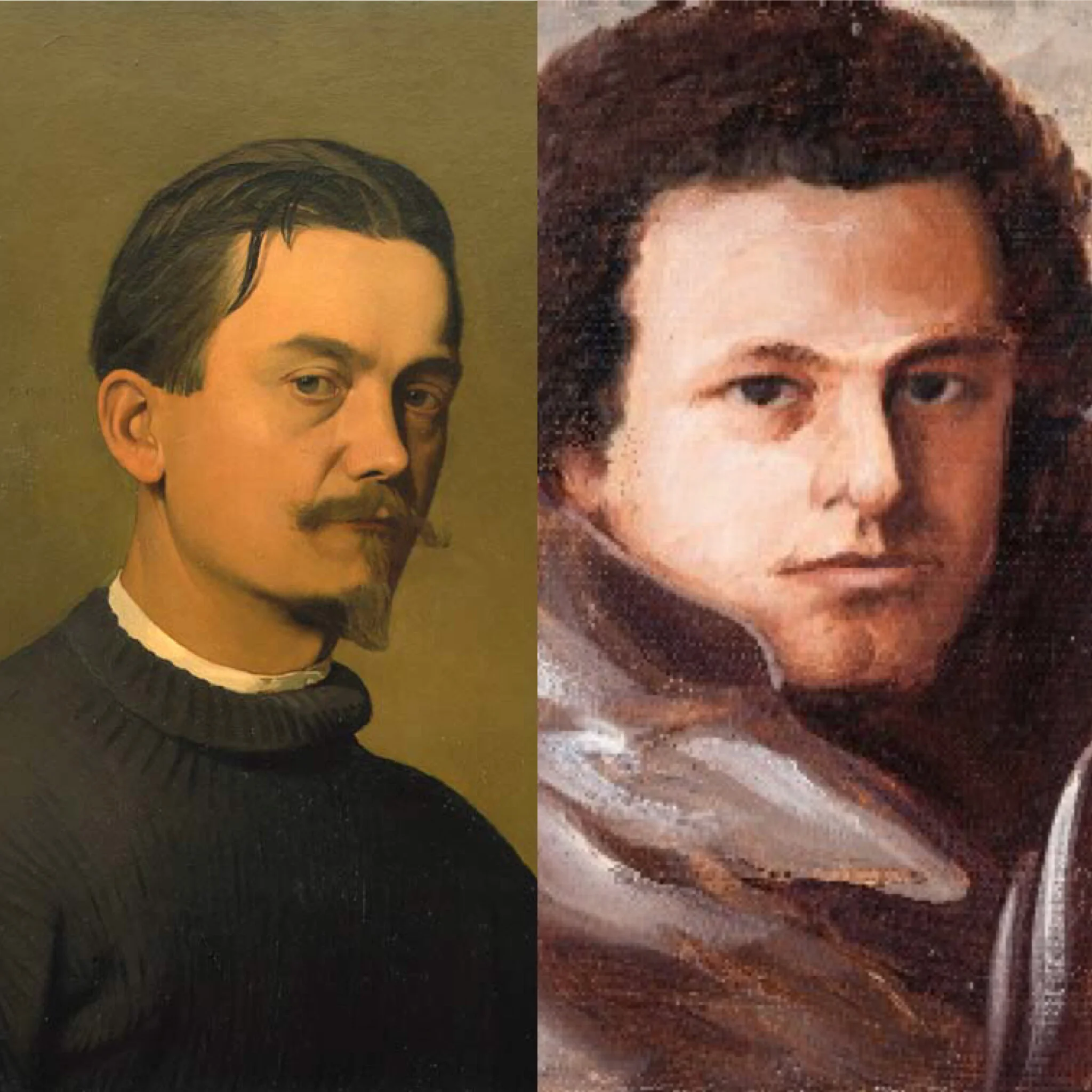

Tan Dun, Composer and Conductor

Tan Dun wanted to create a forest, according to well-spoken cellist Zhilin Wang, addressing the audience prior to the Passacaglia: Secret of the Wind and Birds. Dun, one of China’s most celebrated and visible artistic ambassadors, possesses the enchantment and power to do so. Like a wizard whipping up spells, he brought his fiercely original and poetic compositions to Jazz at Lincoln Center’s beautiful Rose Theater, gracing the podium as guest conductor of The Orchestra Now (TŌN). As a composer, Dun designs a visceral experience in his own, frequently multi-media, works, and has a poised, commanding presence as a conductor, with a strong sense of how music unfolds in space and time.

The Orchestra Now gives hope. Founded in 2015 by Leon Botstein, TŌN is comprised of Master’s Degree students at Bard College, and can be found performing all over the city, including at Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall, and Metropolitan Museum of Art — sometimes for free. Like the student orchestra at Tanglewood, and Miami’s New World Symphony, they’re capable of just about anything, and more than their professional counterparts, they really exude a personal love of music. And they rise to the occasion of encountering international stars like Tan Dun.

The afternoon’s program was perfectly balanced, with Dun’s two pieces buttressed by warhorses from yesterday, opening in a traditional fashion with Czech composer Bedřich Smetana’s symphonic poem The Moldau from Má vlast ("My Homeland"), a series of six pieces inspired by the history, mythology and landscape of the composer's native country. The subject of The Moldau (Vltava in Czech) is its namesake river, and Dun set in motion an unrelentingly even tempo, the spinning sixteenth-note patterns in the woodwinds glassily passing from one group of instruments to another, flowing channels conjoining and building until the music churned like a river.

TŌN’s winds play with a dark, mellow timbre, rounded intonation, and a keen blend. The strings have a honey-like sheen and the violin section displays more rhythmic vitality than many orchestras. They sounds terrific. Not winning any awards in the orchestration department, Smetana’s nationalistic essay might not be at its best in Dun’s Pierre-Boulez-like less-is-more approach (the maestro trusts Smetana a hair too much, perhaps), the folk-like tunes not fleshed out with much bite or grit. But the refinement on display was impressive.

Tan Dun then conducted two of his own compositions. Lauren Peacock, a cellist in TŌN, explained in brief remarks to the audience that Dun’s Cello Concerto from 1994 is one of the Yi series of concerti, three concerti stemming from an “Ur-piece,” Yi 0, a single-movement concerto for orchestra. Dun writes in his explication, “The orchestra is ‘that which already exists’; the solo, the potential which is to be discovered.” Taken altogether, this arch-creation is remarkable. Yi2, a concerto for guitar, melds the classical guitar’s roots in Spanish flamenco with the its Chinese cousin, the pipa.

The cello concerto, titled “Intercourse of Fire and Water” — Tan Dun conceives of things in many layers — atop the same orchestral accompaniment, is a very different experience. The superb Jing Zhao, joined as soloist, playing this formidable showpiece for the cello, amazingly, from memory. Embodying the elements, setting the shape and tone of the piece, she ardently communicates Dun’s exotic musical language incorporating Chinese sounds and techniques, spending a lot of time at the farthest reaches of the fingerboard, the highest part of the cello’s range.

Tan Dun, a master of atmospheric suspense, seems attuned to the dark matter in the universe. A long free-wheeling cadenza, played with abandon by Zhao, is anchored by an omnipresent low drone, like the force of gravity, bowed tirelessly by a single double bass. Throughout, a feeling of tension permeates the room, tension between East and West, tension between soloist and orchestra, between activity and repose, cacophony and silence.

Jing Zhao, Cellist

Shocking dynamic contrasts, if today’s achievements are any indication, are a specialty of Dun’s and TŌN’s. So is embracing outré tools and techniques, such as when Dun writes vocal and breathing effects for the players, such as one moment, pure human exhalation followed by an air-intake in the wind instruments. Most timely was the second act opener, Passacaglia: Secret of the Wind and Birds, premiered at Carnegie Hall in 2015, where instead of banning the use of cell phones, the audience is invited to participate in the music-making when cued to play a recording (of ancient Chinese instruments imitating bird-song) on their smartphones. Later, the orchestra got in on the act, creating the unforgettable image of the entire ensemble incongruously holding up their illuminated phones, the “music” emanating exclusively from them.

A trombone solo, played with declamatory elegance by David Whitwell, introduces the passacaglia theme, followed by a series of variations involving splashy orchestral combos, theatrically stunning shifts from loud to soft, aleatoric moments, and as in the cello concerto, a mixture of Eastern and Western ideas. The percussion section has a starring role in building the momentum, and timpanist Miles Salerni almost steals the show, with his charismatic energy. Dun’s grab-bag of techniques and effects is unified by the eclectic, constantly building, repetition of the theme, an architecture similar to Ravel’s Bolero.

Underscoring the group’s educational underpinnings, it’s terrific how TŌN’s musicians are encouraged to contribute to the program notes, and to speak to the audience to introduce the repertoire. Their enthusiasm for the material, and their craft, is palpable. The concert concluded with an fervent reading of Ottorino Respighi’s early-twentieth-century four movement tone poem The Pines of Rome. As the first orchestral work to utilize an electronic recording (the third movement ends with a recording of the nightingale, as specified by the composer), it’s a fitting pairing with Dun’s Secret of Wind and Birds. The off-stage trumpet solo in the second movement was played with warm lyricism by Anita Tóth, and the third movement’s clarinet solo masterfully played by Viktor Tóth.

Check out these videos to get a feel for the energy of the Orchestra Now, and be sure to add one of their upcoming concerts to your agenda: