***

QUEER PIANOS FOUR HANDS

(Music for Two Pianos/Four Hands by Gay Composers)

by Brian Taylor

***

Benjamin Britten / Introduction and Rondo alla Burlesca, Op. 23, No. 1

In 1939, war loomed. Britten and Pears registered as Conscientious Objectors, and sailed to America. After a few months with friends in Amityville, Long Island, they rented a room in a five-story house (known as “February House”) near the Brooklyn Bridge (eventually felled to make way for the BQE) where W. H. Auden was innkeeper to a rotating cast of characters that included Gypsy Rose Lee.

Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten sailed for America as friends and artistic collaborators. But while in Grand Rapids, MI, their relationship rose to a new level of intimacy.

Britten and Pears were friends with Scottish married piano duo Ethel Bartlett and Rae Robertson, who were described by the Boston Transcript as “the best beloved piano duettists in the world.” The Florida Flambeau wrote that Bartlett was “known as one of England’s most beautiful women.”

Ethel Bartlett and Rae Robertson, married duo pianists.

Bartlett and Robertson premiered Britten’s Introduction and Rondo alla Burlesca at New York’s Town Hall in January 1941 (alongside Milhaud’s Scaramouche). The New York Times described Britten’s Rondo as “interesting” and reminiscent of Hindemith; the Musical Courier called it “adroit and effective.” The Herald Tribune, however, found it “labored and ineffectual.”

Britten’s autograph manuscript for the Introduction and Rondo alla Burlesca.

By June '41, Britten was ready to leave the city, writing in a letter that “New York is the worst, a struggling mass of scheming, shallow sophisticates & the lowest kind of every race under the Sun.” The Robertsons invited Britten and Pears to spend the summer of '41 in Escondito, California.

Benjamin Britten, Aaron Copland, and Peter Pears.

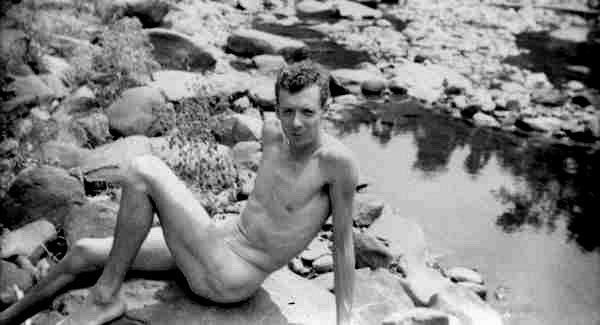

Britten and Pears drove a borrowed old Ford across the continent, picking up hitchhikers, and breaking down in the desert along the way. Once at the Robertson’s house, they spent their days working — Britten with several commissions to fulfill, including Mazurka Elegiaca, Op. 23, No. 2 for Ethel and Rae — and driving to the beach in the afternoon to get “sunburnt” and “drown our sorrows in the big waves.”

But, “an awful lot of energy is wasted in unnecessary emotional scenes,” as Britten put it in a letter to Elizabeth Mayer (July ‘41): Ethel fell in love with Britten, and Rae offered to relinquish his claim to his wife and ‘give’ her to Britten. It seems Britten and Pears were not ‘out’ to their friends.

Britten sunbathing in America.

Britten: “At the moment my greatest wish is to write as much as I possibly can, while I am still able & allowed to - because one never knows how long it will last, & I have such a hell of a lot to want to say.”

That “unhappy summer of 1941,” Britten also composed for the Robertsons Scottish Ballad, Op. 26, for two pianos and orchestra; and in a “marvelous rare book shop” in Los Angeles, he “came across a copy of the Poetical Works of George Crabbe,” and “first read the poem Peter Grimes,” inspiring the first of his many operas often interpreted as dealing with repressed homosexuality, loss of innocence, and the plight of society’s outcasts.

***

Camille Saint-Saëns / Scherzo, Op. 87

1865, Paris — “Saint-Saëns sang and acted the part of Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust with passionate ardour,” wrote Hughes Imbert of Emmanuel Chabrier’s musical soirées in the rue Mosnier: “There was Saint-Saëns, with his Parisian sense of fun and prodigious musical memory. Massenet looking like a repentant Mary Magdalene…Manet, leader of the Impressionists…”

1875, Moscow — Tchaikovsky's brother Modest described Camille Saint-Saëns’s first visit to Tchaikovsky in Russia: “It turned out that the two new friends had many likes and dislikes in common, both in the sphere of music and in the other arts, too. In particular, not only had they both been enthusiastic about ballet in their youth, but they were also able to pull off splendid imitations of ballerinas. And so on one occasion at the Conservatory, seeking to flaunt their artistry before one another, they performed a whole short ballet on the stage of the Conservatory's auditorium: Galatea and Pygmalion. The 40-year-old Saint-Saëns was Galatea and interpreted, with exceptional conscientiousness, the role of a statue, whilst the 35-year-old Tchaikovsky took on the role of Pygmalion. N. G. Rubinstein stood in for the orchestra. Unfortunately, apart from the three performers no one else was present in the auditorium during this curious production.”

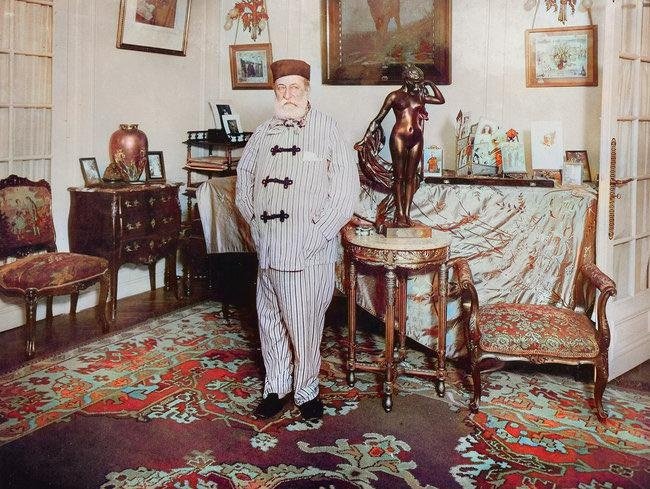

Raised by two widows, great-aunt Charlotte, and mother Clémence, who smotheringly disapproved of all potential girlfriends yet desperately yearned for grandchildren, Camille still lived with his mother at age 40, when (in 1875) he surprisingly married 19-year-old Marie-Laure Truffot.

Arthur Dandelot (in La Vie et l’Oeuvre de Saint-Saëns, 1930): “Saint-Saëns, in his forties, was bathing at the école de natation Deligny with a friend [the Deligny baths had a reputation as a homosexual gathering place], when the latter, having known that the musician wished to marry, put forward the claims of his own sister. Some time later, after the acquaintance was made, marriage was agreed and accomplished the following month.”

An etching of the Piscine Deligny, c. 1850

They had two sons, but in 1878, 2-year old André fell out of a window and died. Six weeks later, the couple’s 6-month old baby, Jean-François, died of pneumonia. They quickly estranged, and in 1881 the composer left on holiday, never to return nor see his wife again.

Saint-Saëns and his wife, Marie-Laure Truffot.

December, 1888 — Saint-Saëns's mother died of pneumonia while the composer was embroiled in disputes in preparation for the premiere of Ascanio at the Opéra. Plunged into suicidal depression and insomnia, within a year he had donated all of his belongings to the city of Dieppe, and embarked for Andalusia, “a night feeling in his mind.”

In Cádiz, he composed the only work from this period, 1889’s Scherzo for Two Pianos: "I am at the mercy of the unexpected; I had no intention whatsoever of writing a scherzo…There are some oddities…Sight-reading it must be fairly painful; it is a piece one should not play until it has been mastered.”

He began traveling in the guise of Charles Sannois, merchant, leading a nomadic existence accompanied by his loyal manservant, Gabriel Geslin, visiting exotic locales like North Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America.

Saint-Saëns became a frequent resident of Algiers ("You board a beautiful ship in Marseille and 24 hours later you land in Algiers; and it is sun, greenery, flowers, life!") where he died on December 16, 1921 at the Hôtel de l'Oasis. He was given a state funeral at Église de la Madeleine, where he had served as organist for 20 years.

***

Francis Poulenc / Sonate pour deux pianos, FP 156

Ned Rorem: “Who will forget that voice, spoken or sung? The harmless venom, the malignant charity? His indiscriminate choice of friends, yet so discriminately faithful to a type; la royauté des sergents de ville! I left a rare and fragrant package of Hindu joss-sticks (purchased the previous month near Tangier's Xoco Chico) with the concierge of Poulenc's Paris apartment. On returning to New York the following week, I found a letter from Francis thanking me for the incense, which he hoped would light the way toward one of les beaux flics that roamed his neighbourhood. The smoke, he said, weaved through his yellow plush armchairs, across the squeaking piano strings, and on out through the casements into the refracting sunlight of the Luxembourg Gardens…”

In 1932, “Winnie” Singer commissioned Francis Poulenc to compose his first work featuring two pianos, Concerto pour deux pianos in D minor, FP 61. Poulenc premiered the work in Venice with his friend Jacques Février at the other piano, and Désiré Defauw conducting the La Scala Orchestra. (Poulenc later performed the work with Benjamin Britten in 1945.)

Flashback —1893, Paris. Lesbian divorcée Winnaretta Eugénie “Winnie” Singer, twentieth child of Isaac Singer of sewing machine fame entered into a “lavender marriage” with the 59-year-old Prince Edmond de Polignac. Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, in their biography of Misia Sert, described the Polignacs as “an extraordinary couple whose marriage had been engineered by Robert de Montesquiou [a count and poet who was Proust's model for the Baron de Charlus]—and a fine arrangement it turned out to be. For while the prince liked men and the princess liked women, they were devoted to each other. The prince was a gifted amateur composer in the Satie style; the princess…heiress to the sewing machine fortune. Theirs was a union the French like to call a marriage of the sewing machine and the lyre. A great patroness of the arts and one of Diaghilev's chief supporters, Princess Winnie, as she was affectionately called, commissioned many compositions.”

The salon of the Polignac mansion on Avenue Henri-Martin became an artistic center of the French avant-garde, introducing work fresh from the pens of Chabrier, d'Indy, Debussy, Fauré, Ravel (the Pavane pour une infante défunte in 1899) and eventually, Poulenc and Stravinsky.

Poulenc’s later Sonate pour deux pianos was dedicated to Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, partners in life as well as renowned piano duo, whom the composer called “Les boys,” and some knew as the “Fizgolds.” Ned Rorem called them “the most important two-piano team that ever was, not only for their diamond-sure executions but for their causing major works to exist for their odd medium.”

Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale

Poulenc began work on the sonata in the autumn of 1952 in Marseille — staying in the same hotel room that housed Chopin on his 1839 return from Mallorca — and wrote of:

“an apocalyptic suite for two pianos (Ah! Messiaen, where are you?) which is exhausting me with its noise and tension."

Poulenc felt that the Andante third movement — inspired by his affection for Lucien Roubert, a married traveling salesman with whom he had a years long tumultuous affair — was the heart of the work.

“Les boys” gave the first performance in London’s Wigmore Hall in November, 1953.

***

Samuel Barber / Souvenirs

March 9, 1980. New York — Too ill to attend his seventieth birthday celebration at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, Samuel Barber receives a phone call from President Jimmy Carter, who was a fan, with birthday greetings.

Flashback — fall of 1941. 19-year old poet Robert Horan, having hitchhiked across the country with his friend Pauline Kael (future film critic for The New Yorker), was hanging out in Grand Central Station when he encountered Barber and Menotti on their way home from the opera. They invited him to their apartment (166 E. 96th St.), and he lived in a ménage à trois with them for the ensuing decade.

Barber set two of Horan’s poems, Menotti, one; Horan wrote criticism, served as Menotti’s secretary, and studied dance with Martha Graham (performing a role in Deaths and Entrances, even suggesting its title). But by 1947, Horan wrote of “a very lengthy, and hopeless tension,” and “the emotional strain of the three-way relationship and the fascinating but rather high-powered personalities in their social world, made life perhaps not quite so serene as it seemed for a highly nervous and very young man.”

Menotti: “It soon became obvious that the apparent success of our triumvirate was illusory.” They sent him to travel abroad (he befriended Truman Capote in Sicily, but soon suffered a nervous breakdown, attempted suicide, and eventually returned to San Francisco), and presently, Barber and Menotti moved on to separate lovers.

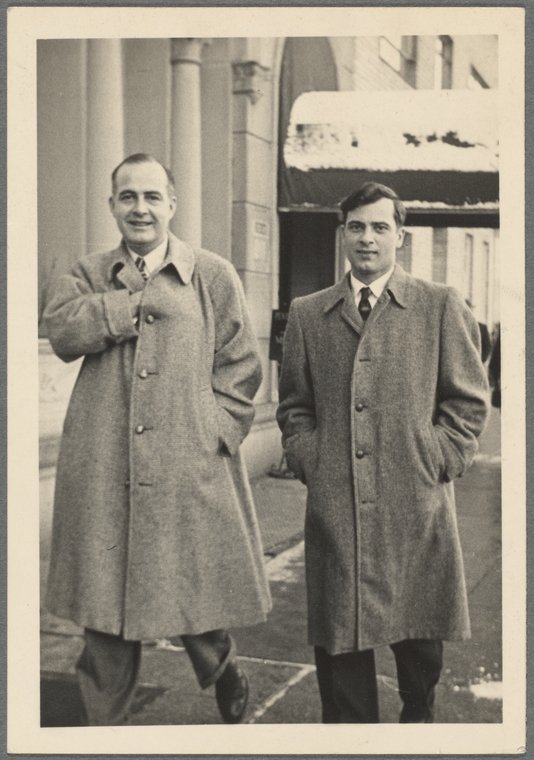

Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, and Gian Carlo Menotti.

Francis Rizzo, an assistant to Menotti: “The improvident Gian Carlo would drink champagne, eat caviar, and run around all over the world. Sam would be stuck with the taxes, the phone bills, the servants — everything!”

Menotti: “I just couldn’t live up to what he wanted me to be.” “I destroyed many of his illusions about me. You see, Sam is very much of a puritan, and he has no interest in petty things, while I have the soul of a concierge.”

Menotti took up with Thomas Schippers in 1950 (whom he met when Schippers accompanied an audition for The Consul — the singer didn’t get the gig, but the accompanist was quickly engaged to conduct the premiere); the same year, Barber was introduced to violinist and composer Charles Turner by Gore Vidal.

Samuel Barber and Charles Turner.

Ned Rorem wrote of Turner: “Chuck emanated neither narcissism nor ferocity, preferring the role of courtier to courted, and speaking quietly of all things cultured … I thought of him always as handsome, green, unpretentious, smart, more than presentable, a mensch.”

Turner played the solo part in Barber’s Violin Concerto under the composer’s baton in Germany 1951 (Pierre Boulez was rehearsal pianist.) He had studied a summer with Nadia Boulanger, and became Barber’s sole pupil of composition. His 1954 Encounter was premiered by George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra.

February 1952, Barber completed Souvenirs: Ballet Suite, Op. 28, a suite of six dances for piano duet for Turner and himself to play together, and to satisfy, as his longtime G. Schirmer editor Paul Wittke described it, his “gather-round-the piano side.”

Turner had suggested something in the manner of Eadie & Rack (Eadie Griffith & Howard Godwin, who played showtunes on dueling pianos at the gay-friendly and desegregated Blue Angel Supper Club on E. 55th; Godwin had played piano for Judy Garland in “Easter Parade;” met Eadie in California and they married; she died in 1956).

Barber’s program note for his “ballet suite”:

“One might imagine a divertissement in a setting reminiscent of the Palm Court of the Hotel Plaza in New York, the year about 1914, epoch of the first tangos; ‘Souvenirs’ — remembered with affection, not in irony or with tongue in the cheek, but in amused tenderness.”

Barber, in a 1956 letter to Turner:

“Much love, sacred and profane, and one very lascivious caress to make you shiver and sigh with deep desire: unsatisfiable…..except with me.”

Fizdale & Gold gave the official world premiere — in their own arrangement for two pianos (only slightly altered from Barber’s original) — in London’s Wigmore Hall, December ‘52, and the U.S. premiere at MOMA, March ‘53. Barber concurrently orchestrated the suite for use as a ballet, although Fritz Reiner premiered that version with the Chicago Symphony in 1953, before the New York City Ballet production materialized.

Charles Turner, remembering Barber:

“I think he thought of himself and his private life as a gentleman first of all, in that rather old-fashioned way that people had of being gay. I think it’s gone out of style now, maybe. But it never did with Sam. In fact I remember him saying to me not long before he died, ‘Well, who would ever know I was homosexual?’”

***

Ned Rorem / Dance Suite for Two Pianos, IV. Epitaph

Ned Rorem studied with Menotti at Curtis — a class called Dramatic Structures — but his relationship with Barber became strained. Barber was not happy when Rorem shared (in his Paris Diary):

“Sam Barber likes the story of a friend, who, seeking an uncontaminated native, went far away to the mountain village near the Swiss border. For reasons unnecessary to relate, he found himself in a sleeping bag with the blacksmith’s child. ‘Oh, I don’t mind,’ said the blacksmith’s child, ‘as long as you give me two hundred lira.’”

Meanwhile, Rorem spent the “very hot” summer of 1949 in Fez, Algiers, where he composed a “sizable Suite for Two Pianos for Fizdale & Gold — which they never played, nor has anyone else (although I orchestrated the Overture years later for my Third Symphony).”

***

Bibliography

Britten, Benjamin. Letters From a Life: The Selected Letters and Diaries of Benjamin Britten. Volume One, 1923-1939. University of California Press, 1991.

Gold, Arthur and Robert Fizdale. Misia: The Life of Misia Sert. William Morrow & Company, 1981.

Gold, Arthur and Robert Fizdale. The Gold and Fizdale Cookbook. Random House, 1984.

Kildea, Paul. Benjamin Britten: A Life in the Twentieth Century. Penguin, 2013.

Laurents, Arthur. Original Story By: A Memoir of Broadway and Hollywood. Applause, 2000.

Pollack, Howard. Samuel Barber: His Life and Legacy. University of Illinois Press, 2023.

Rees, Brian. Camille Saint-Saëns: A Life. Chatto & Windus, 1999.

Robinson, Suzanne. “An English Composer Sees America: Benjamin Britten and the American Press, 1939-42.” American Music, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Autumn, 1997).

Rorem, Ned. The Paris Diary. Braziller, 1966.

Rorem, Ned. The New York Diary. Braziller, 1967.

Rorem, Ned. Absolute Gift. Simon & Schuster, 1978.

Rorem, Ned. Knowing When to Stop: A Memoir. Simon & Schuster, 1994.