REVIEW: Mäkelä and Royal Concertgebouw Seduce Carnegie Hall

Above, Klaus Mäkelä conducts the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. Photo by Chris Lee.

November 22, 2024

“The conductor’s job is to be useful,” Klaus Mäkelä explained to NPR host Ari Shapiro, discussing his appointment as the next Music Director of the storied Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The 28-year old maestro from Finland — a chief exporter of influential conductors, thanks to strong childhood musical education and public funding of arts organizations — made usefulness seem divine in his second appearance at Carnegie Hall, in the first of two concerts with the other legendary orchestra he will soon helm, Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra.

If conducting technique was an Olympic sport, Mäkelä gave a medal-worthy performance. Perhaps the clearest conductor I have ever seen, embodying in equal parts the physicality, and spirit, of the music, he propelled the music’s rhythmic and dynamic energy into orbit, while also infusing it with emotional character. Svelte and debonair — and impeccably tailored — he does so without losing that Stokowski silhouette.

Mäkelä wielded the Royal Concertgebouw’s renowned ensemble (in their first intercontinental tour under his baton) like a mighty instrument — a virtuoso at the console of the world’s greatest pipe organ. And the musicians that call Amsterdam’s legendary concert hall home harnessed Carnegie Hall as if it were an extension of their instruments.

Pulitzer Prize-winning American composer Ellen Reid’s Body Cosmic, a Carnegie Hall co-commission, began the evening. A meditation on the composer’s experience of pregnancy and giving birth, this autobiographical two-movement tone poem marking the composer’s residency at the Concertgebouw for the 2023–24 season was given an auspicious first reading by Mäkelä and the Royal Concertgebouw.

Ellen Reid greets the performers at Carnegie Hall. Photo by Chris Lee.

The first section, Awe / she forms herself, unfolded from rising, sinewy tendrils, like strands of DNA. The murky orchestration panged, drooped, and bended while expanding, like a mass, or a universe. It conjured the sensation of a flower blooming. The harp and chime gently tolled the passing of time, the waiting. Next, in Dissonance / her light and its shadow, a violin cadenza heralded a new spirit, its tremolo hinting at colicky cries. Eventually, warm flutes and the imposing, trilling brass section took a spasmodic journey from needy distress to a vista of joyful wonderment.

Violinist Lisa Batiashvili joined as soloist in Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 63. This postcard from the edge of Prokofiev’s resignation to Russia after a decade in the West was a vivid, cautionary fairytale in the hands of the balletic Batiashvili and disciplined accompanist Mäkelä. The 1935 score is a turning of the page in Prokofiev’s output — a harbinger of a more conservative, Soviet-imposed late period, and a look back, a summation of his experimental time among the Parisian neoclassical and avant-garde.

Photo by Chris Lee.

Batiashvili’s ravishing tone was rich and expressive at both extremes of the fiddle, from her husky G string in the first movement’s brooding and frosty opening to her operatic E string in the slow movement. Her intonation was razor-sharp in the shifting harmonic thicket of athletic double-stops, and Mäkelä maintained a pulsing tautness between the insistent, threatening bass drum and the soloist’s flying sixteenth-note runs. The bittersweet middle movement, Andante assai, was played like chamber music, and guided by an arc both ironic and mythic. The rueful, Spanish-tinged finale drove to a sizzling conclusion, the colorful and supportive woodwind section nestled under Batiashvili’s wings. The encore was an ensemble effort, too: a poignant arrangement of Bach’s Chorale Prelude on "Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ" for violin and strings.

Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 2 in E Minor, Op. 27, is a double-edged sword. The composer’s 1907 comeback following a nervous breakdown after the failure of his first symphony is a crowd-pleaser abounding in indelible tunes. But it is long-winded and syrupy, requiring a deft hand to keep its delicious treacle from turning rancid.

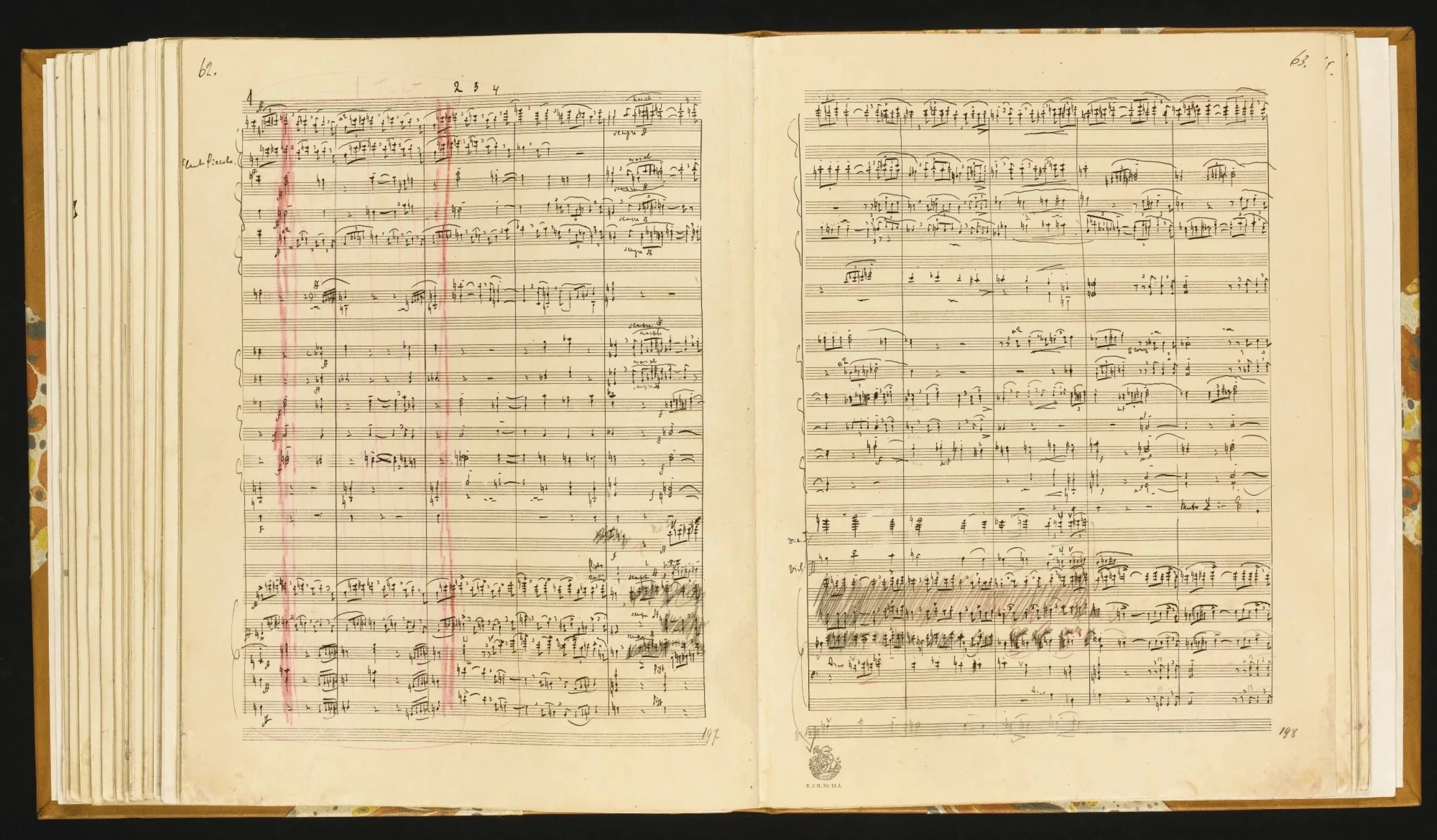

Autograph manuscript of Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony.

Mäkelä drove a swaggering, extravagant account, not as cinematic and crooning as Eugene Ormandy’s 1951 recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra, nor as hilly and windswept as Mariss Jansons’s interpretations, but lustful, hungry, and seductive. Mäkelä fashioned the second movement, Allegro molto, into a swashbucking adventure, brisk and journeying (as opposed to Jansons’s earthier, Mahlerian feel), fleetingly mesmerized by the distraction of romance.

The RCO was flawless — from the focused, creamy clarinet solo in the Adagio slow movement to an uncommonly expressive horn section and crisp, articulate low brass. The orchestra’s mind-meld with Mäkelä allows them to play with flexible rhythmic detail, and intricately balanced dialogue, as in the stormy buildup to the climax of the first movement’s development section. Mäkelä avoids any slack between the first violins and the low brass, and draws pointed entrances from all angles, resulting in lean, chiseled textures.

Perhaps it is the American in me (a product of its vastly less rigorous music education) to desire a pinch more individuality, and a hair more introspection in the lyricism. Mäkelä is just beginning his swashbuckling adventure, and who knows how the plot in Chicago will unfold. With results like this, I’m certainly along for the ride. Listen and decide for yourself. (The concert was broadcast and available to stream from WQXR.)

***