REVIEW: Pacifica Quartet's Portrait of America at 92NY

Above photo © 92NY.

November 13, 2024

Grammy-winning Pacifica Quartet painted a monumental portrait of the United States in their recent American Snapshots: JFK, Vietnam, and Ellis Island at 92NY, indemnifying music from two of America’s darkest moments — from two of America’s worthiest twentieth century composers, Samuel Barber and George Crumb — with a symbol of its optimism and possibility, Antonín Dvořák’s “American” Quartet.

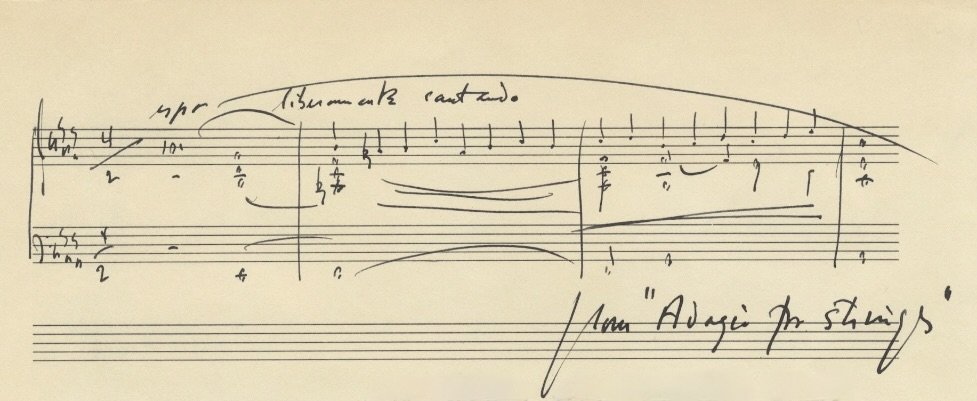

“Whenever the American dream suffers a catastrophic setback,” Alex Ross writes in The Rest is Noise, “Barber’s Adagio for Strings plays on the radio.” A spectacular example of creative inspiration, twenty-six year old Barber composed his second string quartet, Quartet in B Minor, Op. 11, in 1936 in a lake town in Austria while studying in Rome. The young composer knew he had a winner in the anachronistic yet sincere second movement, describing it in a letter as “a knockout!”

The string quartet, as a medium, bares a composer’s purest statements (see Beethoven, Bartók, or Britten), balancing expression with classical rigor. And no composer embraced creative restraints better than Barber, who specialized in setting literary poetry, and was sneered at as traditionalist (while attracting the most impressive of champions, from Vladimir Horowitz to the Metropolitan Opera). The famous middle movement, Molto adagio — the first American music Arturo Toscanini broadcast on the radio with his NBC Symphony in the arrangement for string orchestra — became seared into the American psyche, but the music that precedes and follows it in the context of the original piece is rarely performed. Pacifica’s performance was transfixing and enlightening.

The outer movements mirror each other, tightly motivic and veering from nervous tension to the questioning repose of simple triads. Pacifica poured it forth in generous, long lines with a riveting ebb and flow. Especially riveting was the moment when cellist Brandon Vamos’s bow broke mid-phrase; a back-up was nearby and the brief interruption seemed of a piece with Barber’s music, which moved in fits and starts.

Pacifica refreshingly eschews the contemporary trend to non-vibrato; this foursome vibrates lavishly, resulting in a plum, iridescent sound. Each player contributes personality to a cohesive unity, reaching wrenching intensity in the high-peaked climax of the Molto adagio. This intensity presaged the shock of George Crumb’s devastating response to the Vietnam War, Black Angels: Thirteen Images From the Dark Land.

Photo © 92NY.

Completed on a Friday the thirteenth in 1970, Crumb’s Black Angels is quintessentially avant-garde. The composer’s trademark, beautifully hand-drawn, calligraphic score calls for an “electric string quartet” and a variety of extended techniques, including various percussion, vocalization, and even whistling. The numbers thirteen and seven figure prominently, shouted or whispered in various languages, and the three sections, Departure, Absence, and Return, create a symmetrical arc. Crumb both references tradition — quoting the Dies Irae and Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden” Quartet — and defies it, in a shattering assessment of the trauma of war.

The Pacifica Quartet attacked fearlessly, diving into Thenody I: Night of the Electric Insects, grotesquely conjuring enemy helicopters swarming above. They gamely channelled the Sounds of Bones and Flutes with rhythmic tongue clicks, clackety col legno bowing, and obscure prayer stones. Eerie bowed tam-tam and ominuous scraping hypnotize in Lost Bells and Devil-music, a solo cadenza for first violinist, Simin Gantra.

Gamatra, second violinist Austin Hartman, and violist Mark Holloway conjured a séance in Pavana Lachrymae holding their instruments vertically, “like a consort of viols.” In Threnody II: Black Angels! a buzzing hiss reached fever pitch, building to menacing counting in German; as the numbers progressed to dreizehn, they gradually diminished to a whisper, suddenly the assaultive slam of a tam-tam. The threat retreats into the distance as we hear a mournful Sarabanda de la Muerte Oscura, and a reprise of earlier lost bells, bones, and flutes.

After a 13-second pause, God-music — bowed crystal glasses accompany the doleful cello, frozen in time, recalling Messiaen — and then Ancient Voices, metallic and echoing, Threnody III, in which the Electric Insects return, and finally a reprise of the ghostly sarabande.

This mystical visit to the foxholes of Vietnam was assuaged by a return to an earlier, more hopeful time in America. Pacifica soared in Dvořák’s String Quartet No. 12 in F Major, Op. 96, composed in 1893 during the Czech composer’s residence in the States, and infused with the pentatonic flavors of African-American Spirituals and Native American folk music. Proving uncommon versatility, Pacifica transitioned from the painful discomfort of Crumb’s nightmare to the vibrant dancing and yearning song of Dvořák.

An encore of the first movement of Russian-American composer Louis Gruenberg’s Diversions, Op. 32, was a refreshing dessert. Here, as in Dvořák, exchanging melodies in bustling conversation, handing flowing phrases and pointed pizzicato from one player to the next, Pacifica is the model of an activated ensemble — ears and eyes present, making room for one another, making the music always go somewhere. Would that modern-day America would follow suit.