REVIEW: Orchestra of St. Luke's Looks at Classical Style

APRIL 19, 2019

BY BRIAN TAYLOR

Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Grammy-winning chamber orchestra based in New York City since 1974, gave Carnegie Hall audiences a brilliant essay on Classical tradition, through the looking glass of the Neo-Classical. A delightful celebration of the symphony and its offspring, it was the perfect program.

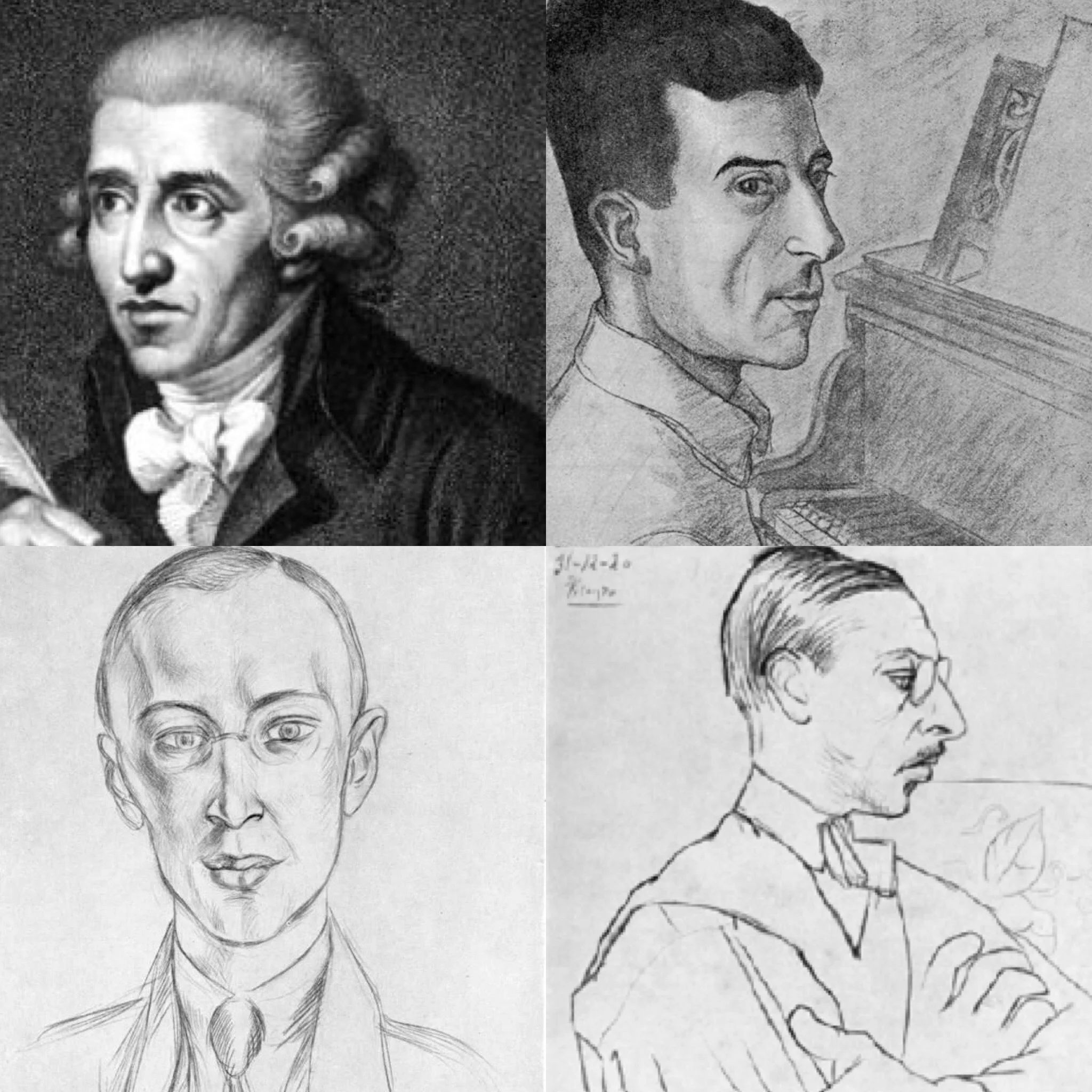

Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1, which the composer called his “Classical,” bears his distinctive voice, but writing in the style of Haydn. Composed in 1916, this deliciously tuneful miniature symphony winks at the listener. Prokofiev had already served up his “bad boy” side, avant-garde experimentations such as Sarcasms for piano. Here, the young composer snaps back at pearl-clutching critics (like his conservative teacher Alexander Glazunov) and invents a new trend in twentieth century music: Neo-classicism.

Under the assured baton of Conductor Laureate Pablo Heras-Casado, OSL is perfectly at home in this uptight, tricky score. The violins have a velvety sheen as they trade galant quips in the festive first movement, dance elegant steps in the genteel Larghetto, or chase antics in the vivacious Moto vivace; they have a close-knit rapport. The woodwind section is in top form, each flute, oboe, and clarinet solo more sparkling than the last. The bassoons shine especially in the first movement’s staccato motor. Mr. Heras-Casado’s account is an exercise in arrival points, especially when they come as a surprise.

Hélène Grimaud, self-described Renaissance woman, joined the orchestra as soloist in Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major, his 1931 answer to admirer George Gershwin’s sensation Rhapsody in Blue. Ravel flirts with blues and jazz, but filters it nicely into a classical concerto mold. The enduring quality of Ravel’s score is that it can expand and contract; it’s inspired by whimsy and improvisation, but every note is locked solidly into a sturdy framework, like a skyscraper designed to bend in the wind.

In Ms. Grimaud’s hands, the first movement, a riveting blend of jazzy musing, motoric and suspenseful agitation, and soaring, feverish song, was a stormy affair. Some pianists might, for example, play the movement’s driving, rhythmic material, which begins low in the instrument after the lyrical second theme, with the relentless evenness of an clacking engine. But Ms. Grimaud makes a long, sweeping sprint to the first cadenza-like outburst that leads to a brash, two-handed restatement of the opening theme.

Ravel gives the orchestra a workout in the concerto, too. The OSL brass, in particular, displays indefatigable chops in the first movement’s buckaroo-like main tune. The woodwinds and strings provide tactful phrasing and warm colors in the tender second movement — slipping in after a lengthy Mozartian solo for the piano — a simple oom-pa-pa accompaniment and a long, never-ending melody in the right hand. Its austere texture belies exquisite tension and harmonic pinpricks, glassine like a crystal.

Ms. Grimaud poured too much chocolate sauce on the Adagio assai, taking Ravel’s marking of espressivo as license to overly romanticize, her two hands walking along divergent paths. As the plaintive melody unspools into delicate decorations atop caressing woodwinds and glowing strings, Ms. Grimaud turns Ravel into Chopin, with generous rubato at the seams of each phrase — a mannerism that becomes predictable.

A refreshing toccata-like Presto brings the work to a rollicking finish. Ms. Grimaud’s vigor and energy in the driving perpetual motion is unimpeachable, repeated notes flying from her fingers with laser-like precision. Mr. Heras-Casado and the taut ensemble of OSL have no trouble keeping pace with Ms. Grimaud’s individualistic, vivacious tear through this versatile showpiece.

Igor Stravinsky was a prominent practitioner of the Neo-classical. His light-as-air Suite No. 1 for Small Orchestra is a 1925 orchestration of material he composed in 1914-15 as teaching pieces for young people. These little miniatures have infectious appeal and serve as little incubators for the Rite of Spring composer’s forthcoming move into the arid, ironic world of The Rake’s Progress. Not merely an amuse-bouche for the Neo-classical music he would later explore in more depth, it’s a lean little sinfonietta, nodding to the expectations and customs of the sonata-based format of yore.

The first movement, a docile Andante, finds Stravinsky painting a gauzy, pallid calm. The OSL, led with aplomb by solo oboe, assailed the angular rhythms and quick back-and-forth of the Napolitana. The acerbic Española proved more of a struggle for the woodwind section’s normally impeccable intonation. The impish Balalaïka marched along with a punch.

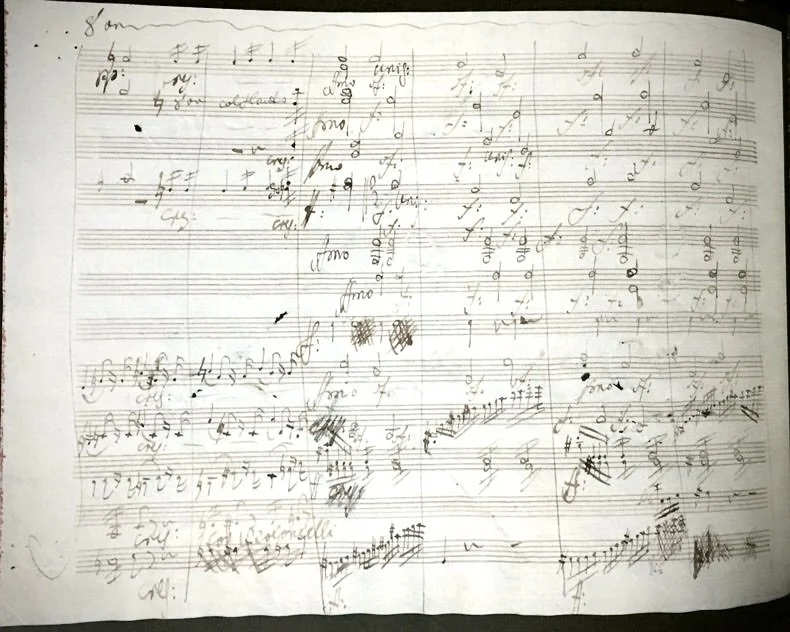

“Papa” Haydn’s Symphony No. 103 in E-flat Major, the so-called “Drumroll,” was composed in 1795, and plays the role of classical model here. The famous timpani roll that begins the piece is open to interpretation: Haydn did not indicate any dynamics. Tonight, Mr. Haskins attacked it firmly, then died away in an even, theatrical diminuendo, like the rising of a curtain; the dim stage lights slowly brighten on the slow introduction to the first movement. Haydn’s penultimate symphony is chock full of rhythmic wonder and motivic invention, and looks ahead to the innovations of a promising pupil named Ludwig.

The second movement, a set of double-variations, opens with a stately passage revealing the OSL’s noble, darker hues. The mood lightens as it goes along; a sense of hope is conjured in a gracefully played violin solo. The timpani soon reminds us of its presence, and the orchestra returns tutti to the shadowy main theme, before a resolution is reached, and the music grandly arrives to a new key, solo flute riding atop like a glorious flag waver, played tonight with flawless panache. Mr. Heras-Casado could have sharpened the edges of the movement’s Sturm-und-Drang, although the timpanist, eager to earn his keep in the titular role, did not shy from his duties.

The third movement, an earthy, humorous Menuetto, also paves the way for Beethoven. The OSL plays each return of the weighty theme with the gusto of a jaunty, swinging dance. The Trio transports us from earth up to heaven, and the orchestra emphasized this contrast, creating a sweet respite in the clouds. The finale, Allegro con spirito, rode a wave of adrenaline to a triumphant finish. Mr. Heras-Casado kept the lid on the dynamics teapot, not letting the volume build too soon, thus ratcheting up the sense of release in the final cadences. The movement’s driving tempo and relentless sense of joy put the finishing touches on this exhilarating performance.

***

OSL’s upcoming performances:

Lady in the Dark, Part of OSL with Mastervoices

April 25 - 27, at Carnegie Hall

Mendelssohn the Prodigy, Part of Chamber Music Series

April 28 at the Brooklyn Museum