REVIEW: American Classical Orchestra Celebrates 40 Years

September 18, 2024

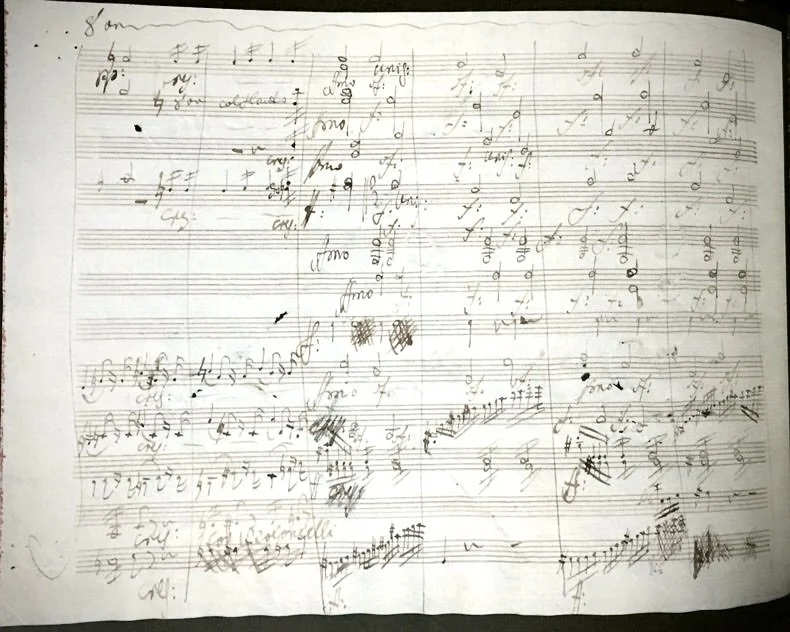

The American Classical Orchestra opened their 40th season on a joyful note. Under the baton of Artistic Director Thomas Crawford, Wednesday’s concert at Alice Tully Hall celebrated the audience as much as the venerable period-instrument ensemble itself. Serving up one of classical music’s great crowd-pleasers, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, Crawford combined a light, breezy touch with heartfelt investment in the music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

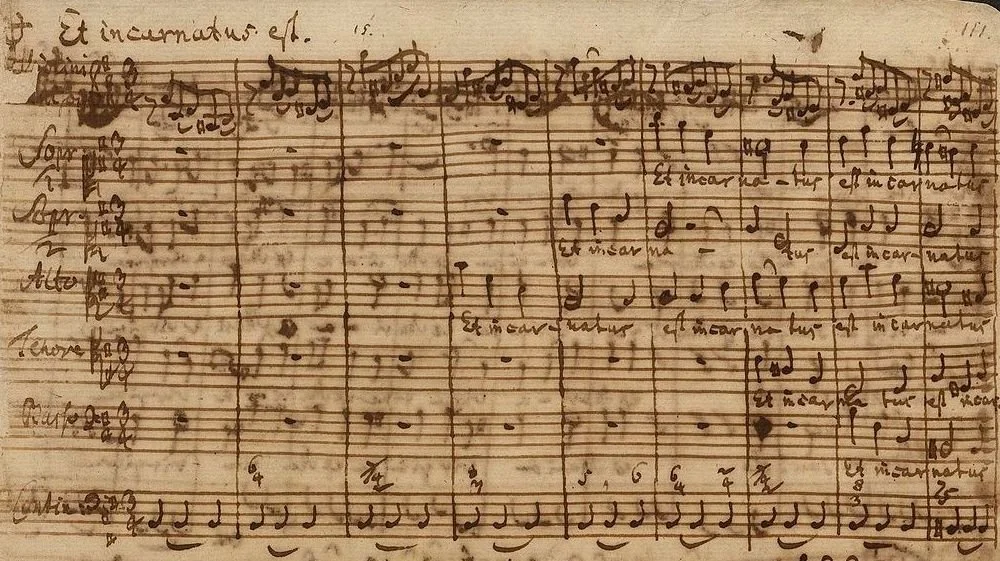

Beethoven’s lyrical fourth piano concerto was originally intended as first course, but had to be rescheduled; a short assortment of appetizers was culled together and substituted nicely. First, an unexpected aperitif: the Molto allegro first movement of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550. Number forty (in honor of the orchestra’s fortieth, as Crawford explained) afforded the orchestra a chance to dig its teeth into a piece they know well, and also set the stage for Beethoven’s injection of pathos into the classical era.

Sandra Miller, Thomas Crawford, and the American Classical Orchestra.

The concert had the spirit of a salon. Crawford supplied bubbly commentary throughout. He lauded ACO’s wind section, pointing out that in Mozart’s day, the woodwind instruments were still in a state of evolution, and their use was constantly innovative; the oboes, clarinets, horns, and bassoons beguiled with an airy lark evocative of the Austrian countryside, the Andante from Mozart’s wind Serenade, K. 388.

Schubert’s Lied-like Entr’acte No. 3 from Rosamunde, D. 797, served as bittersweet palette cleanser and more prominently featured ACO’s strong string section, before we returned to Mozart. Flautist Sandra Miller anchored the Andante in C Major, K. 315, a movement for solo flute and orchestra, with stylistic elegance and a dolce tone. A complete flute concerto, or something more flashy, might have felt more festive.

But, all of this was mere prelude to the main event, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92. Before intermission, Crawford led the audience on a quick and entertaining tour through the symphony, commenting on (often amusingly) brief excerpts. He has a wonderful knack for communicating musicology to the layman, making active listeners of the audience and eliciting knowing smiles when discussed passages are played in context.

The first movement’s suspenseful introduction, Poco sostenuto, built dramatic anticipation with surprising harmonic shifts and blossoming ascending scales until it exploded into the ensuing Vivace, which made clear that this was to be an urgent, driven account of the score. Crawford emphasized broad gestures, winked at Beethoven’s wit, and relished in the ACO string section’s robust, polished sound. The trumpet section proved indefatigable. Timpanist Dan Haskins’s calf-skinned kettle drums buttressed the piece’s rhythmic bones with plush accents.

Thomas Crawford and the American Classical Orchestra.

The Allegretto moved along resolutely and determinedly, capped by yearning pleas from the flutes, oboes, and clarinets. The scherzo was dogged and insistent at first, relenting into the glorious trio section which featured ACO’s noble horns and a light touch in the lilting, yet reflective, lyrical theme. Crawford paced the symphony expertly, saving just enough energy for the exhilarating finale, Allegro con brio, which beamed with the zeal of a rustic Oktoberfest dance, and a bombastic display of fireworks.

***

ACO’s next performance at Alice Tully Hall: