REVIEW: Orbiting the Jupiter Symphony

May 8, 2024

Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 in C Major, K. 551 is a force of nature, a masterpiece that seems an integral fabric of the musical galaxy (for those born after 1788). Like the weather and the sky, it continues to surprise and awe. Known better by its moniker Jupiter, the piece formed the nucleus of the final concert of American Classical Orchestra’s 39th season. Thomas Crawford led his venerable period instrument orchestra in an evening of selections, winkingly united under the theme Astronomical, that brought telescopic perspective to the orbital trajectories, the half-lives, of musical compositions.

With whimsical air and a light touch, Crawford welcomed the audience in an insightful preview of the evening’s horoscope. He downplayed the “Astronomical” motif, but there’s more to it than gimmick. German-Norwegian Johan Daniel Berlin, thirty years younger than Bach, and German-Londoner William Herschel, another generation younger, were renaissance men in the period when Baroque was evolving into Classical. They embodied the Enlightenment — not only composers, but scientists, and as luck would have it, astronomers.

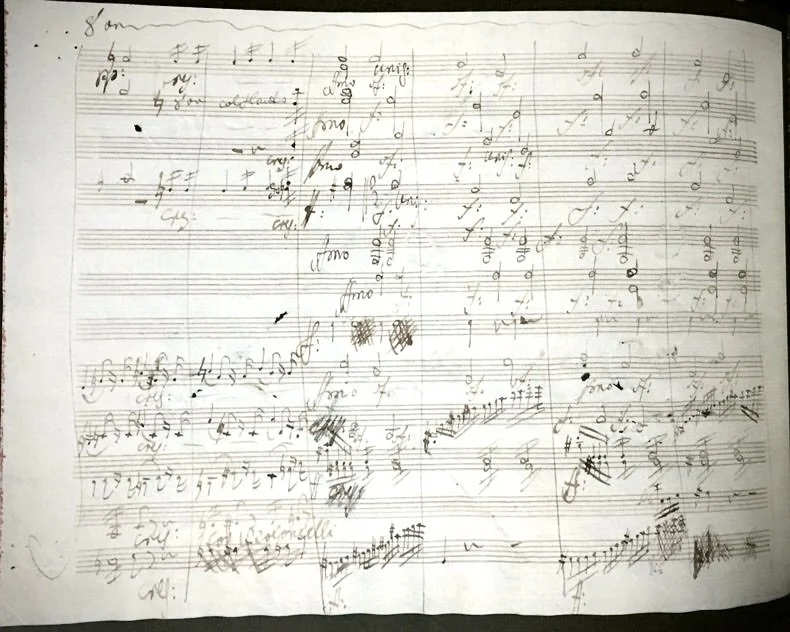

Thomas Crawford, harpsichord, and American Classical Orchestra.

Berlin’s Concerto á 5 in A Major, a concerto grosso showcasing virtuoso solo violin, played with verve and panache by ACO’s concertmaster, Jessica Park, set the tone with rising and falling arpeggios and scales conjuring the image of a night sky of streaking comets and shooting stars. Herschel’s Oboe Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major, starring stellar oboe soloist Gonzalo Ruiz, mimics a da capo aria from Baroque opera, the oboe assuming the coloratura castrato role in a fiery retort to the heavens. Rightly so, space and time have rendered both works obscure; Herschel’s discovery of the planet Uranus remains a more notable contribution to history than his musical compositions.

C. P. E. Bach’s Symphony No. 5 in B Minor, H661 Wq 182/5 is a different phenomenon. Exploding with originality, this is an outburst of the “empfindsamer Stil” aesthetic movement that ushered in a new “sensitivity” — impetuous drama and emotional contradictions. Crawford led an adventurous trek through the three movement symphony, which blends solid German engineering (inherited from the composer’s expert father) with a passionate exuberance pointing the way to the Romantic.

The impetus of the program, Mozart’s Jupiter, was worth the journey. Crawford’s energized conducting inspired a detailed, yet vivacious reading of the score. Flying fingers and buzzy warmth from the antique bassoons; heroic accuracy from rustic, militaristic horns and trumpets; piercing thunder strikes from calf-skinned kettle drums. The ACO strings illuminated the inner movements with long-lined warmth.

Crawford emphasized the Sturm und Drang in Mozart’s sensibility, achieving stunning dynamic contrasts and shifts of sentiment, and roundly balancing the push and pull of tension. The second movement, Andante Cantabile, had the off kilter light of a total solar eclipse, and Crawford launched the fugal finale, and its climactic, celebratory coda, into orbit.

***

Brian Taylor is a pianist, conductor, composer, writer, and piano teacher in New York City.