REVIEW: The Knights Slay Beethoven's Fourth and Assorted Rhapsodies

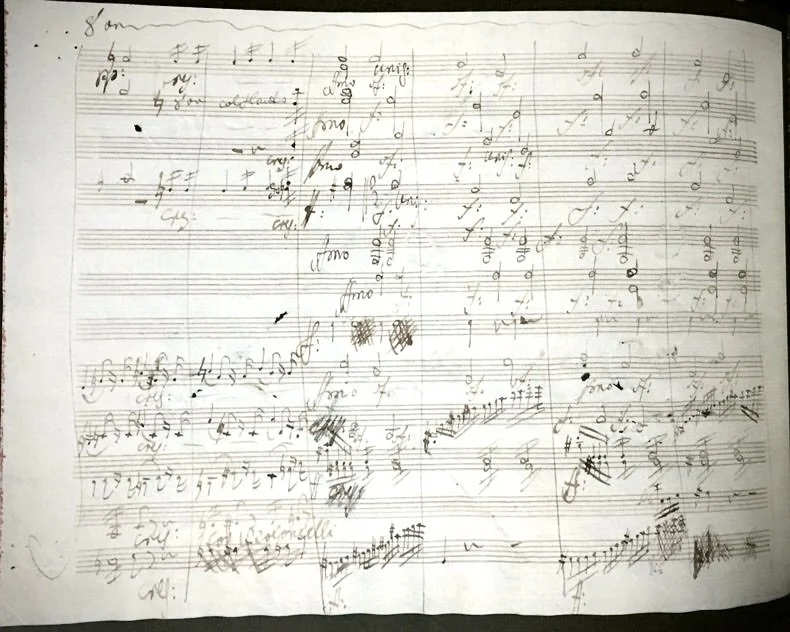

Above photo by Jennifer Taylor.

October 24, 2024

The centennial of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue continued into its fourth quarter with The Knights’ latest at Carnegie’s Zankel Hall, featuring a world premiere as part of their multi-season Rhapsody-themed commissioning project. The Brooklyn-based orchestra welcomed pianist Aaron Diehl for a unique take on Gershwin’s familiar piece for piano and orchestra, a new composition for the same combination by Michael Schachter, balanced, in a stroke of programming ingenuity, with Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony.

Conductor Eric Jacobsen led his sprightly band in an energized rendition of Blue’s orchestral passages (arranged by Michael P. Atkinson); the opening clarinet glissando was as smooth as ever, and from zany trumpet solo to zippy string melodies, peppy phrasing and sharp crescendos lent a zaniness hinting at flappers and Steamboat Willie — not unlike how Gershwin’s 1927 record sounds to modern ears.

The beloved piece’s hundredth anniversary has occasioned innumerable performances and invited reexamination of the music’s significance, of Gershwin’s intentions and continued relevance — bringing fresh interpretations aplenty. One such approach — since the composer is said to have largely improvised the piano part at the Aeolian Hall premiere — sees pianists embellishing and ad lib-bing portions of the piano part, instead of playing it note-for-note. Lee Musiker, soloist with the New York Pops last February, made a revelatory case for taking such liberties. He jazzed up the solo part by expanding and enriching Gershwin’s ink, extending the harmonic progressions in well-plotted arcs, and blues-ily digging into every written detail.

Diehl took a very different approach, dispatching Gershwin’s written passagework glibly before jettisoning it altogether, veering, like a record skipping, into stream-of-consciousness improvisation. Diehl’s command of jazz styles was fully evident: Fats Waller stride, fist-fulls of Thelonious Monk, Latin funk. He steered back to Gershwin only when it was time for the orchestra to fortify us with juicy horn playing, spirited drumming, and swooning violin portamentos in the iconic lyrical theme.

Photo by Jennifer Taylor.

The pianist’s flights of fancy narrowly avoided derailing his sense of purpose, and the orchestra’s entrances seemed forced. But, perhaps this fly-by-pants energy recaptured the riskiness of Gershwin’s legendary first performance.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 in B-Flat Major, Op. 60, was more convincing. The 1806 masterpiece amounts to something of a deep cut, hiding in plain sight between the “Eroica” and the ubiquitous Fifth. Jacobsen led a vivacious, detailed account, beginning with a mysterious Adagio introduction evocative of an awakening, an exquisitely paced buildup of anticipation and release, exploding into Allegro vivace. The second theme’s crisp solo woodwinds had a dark, cautionary character.

The Knights delivered on the extraordinary power of the Adagio slow movement. Jacobsen harnessed the Brucknerian textures — sforzandi employed with stentorian strength, and a consistency of articulation that supplied rhythmic propulsion and urgency — and the scherzo, Allegro vivace, surrendered to a delicious Trio section, Un poco meno allegro, with dolce grace notes in the violins, and taut dialogue between bassoons and flute. The thrilling finale, Allegro ma non troppo, revealed Beethoven the rock ’n’ roller. The bassoons performed feats of oral athleticism in their soli false return to the first theme, defying any fear that the tempo was a little troppo.

A pair of world premieres followed intermission, first an arrangement by Atkinson of three tracks improvised by Keith Jarrett on his 1987 clavichord album Book of Ways. Atkinson gives an orchestration masterclass, taking Jarrett’s Steve Reich-like layering of jagged rhythms and open, repetitive harmonies that pull in different directions, and trickily translates it to winds, strings, and percussion, and Diehl on mostly supportive harpsichord.

The middle movement, a plaintive, heavily ornamented troubador-like melody anchored by slow strumming, was animated with new flavors in Atkinson’s clever scoring. The Knights’ keen listening and attention to pure intonation created colors that shimmered and shifted in temperature. I worried that Gustav Highstein’s haunting oboe solo better conveyed the spirit of the original than Diehl’s pert ornamentation at the harpsichord.

Atkinson’s arrangement enhanced the shape of the third piece — which starts with a bright celebratory choral texture, but gets stuck in a spiral in Jarrett’s original — using judicious scoring to add a storytelling element. Crisp ensemble made logical sense of rhythms that free-fall on Jarrett’s album; the range of dynamics available to the orchestra adds shape and build to the repetitive patterns that sound static on the clavichord.

Photo by Jennifer Taylor.

Composer Michael Schachter intended Being and Becoming, Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra, “to take the context of [Gershwin’s] rhapsodic project as impetus to reckon with the here and now … tuneful and vernacular, moving more by the hot thrill of impulse than the cool logic of austere design.” Schachter’s point of view speaks with the eclectic palette of today’s musicians and audiences, journeying from Brad Meldau-like sparkling pianism and nervous ennui, flashing memories of Bernstein’s purple profundity to, eventually, a Radiohead-inspired dancing groove, via an ominous saxophone solo (played with menacing clarity by Todd Groves).

Diehl demonstrated clear focus in the rangy piano solo, embracing its balladeering and technical adventures such as reaching into the piano strings, muting them for a percussive effect. The piece’s denouement brought Dave Brubeck to mind, and echoing Gershwin’s Rhapsody, arrives at a big voluptuous tune, which the orchestra echoes dramatically. Schachter’s rhapsody conjures the mood of today’s America: a variety of influences, anxieties, and desires struggling for unifying resolution.