REVIEW: Parlando's Powerful Music of Night

September 26, 2024

The enduring theme of night music — the nocturne — was explored in the latest Merkin Hall performance by Parlando. Conductor Ian Niederhoffer, who founded this promising chamber orchestra in 2019, conceived and led a packed house through an insightful and captivating rumination on the musical night-scape.

Niederhoffer ingeniously emphasized — in generous spoken introductions to the pieces — the heightened emotions experienced after sun down. And the evening’s repertoire captured some of the various ways composers have been inspired by night to harness those intense feelings.

Mozart might be the earliest composer to wed that association with western musical tradition, such as in the Serenata notturno, K. 239, and most famously with the title Eine kleine Nachtmusik. The nocturne became a trope of character piece, in solo piano works by John Field and Chopin. Felix Mendelssohn found occasion for a nocturne in his incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and later, Gabriel Fauré (who penned his own nocturnes for solo piano), in his music for an adaptation of Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice by Edmond Haraucourt called Shylock, found dramatic use for the genre.

Parlando began the evening with the Nocturne from The Shylock Suite, Op. 57, which begins placidly, and soon swells with yearning. Niederhoffer’s strengths on the podium were apparent from the start, as he skillfully sculpted a love scene from the short piece’s sprawling, long-unspooling melody. He drew from his string orchestra a tone color as pure as the night sky and a singing line that blossomed into deeply felt passion.

Fauré at a rehearsal for Shylock at Trevano, 1909.

We shifted to humanity’s relationship with the natural world, for a different perspective on night, in Tōru Takemitsu’s Toward the Sea, a 1981 work commissioned by Greenpeace to benefit the Save the Whales campaign. This three movement work for solo alto flute (played beautifully by New York Philharmonic flutist Yoobin Son), harp (Parker Ramsay), and strings took inspiration from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, or the Whale. The first movement, The Night (which is followed by Moby Dick and Cape Cod), submerged the listener in mysterious, dreamlike harmonies, awash in a liquid approach to time. Like the ocean itself, the music does not seem to have a beginning or end — there are no hard edges or angles. It envelops you. Niederhoffer skillfully navigated his silky, plush string orchestra through these murky channels, allowing Takemitsu’s warm sounds to ebb and flow, seemingly freely, around Ramsay’s delicate and unforced harp arpeggiation, and Son’s silken, earthy timbre, that seemed to belong to neither East nor West.

Yoobin Son and Parker Ramsay remained on hand for a work not necessarily conceived as a nocturne, but perfect for the occasion: the Andantino second movement from Mozart’s Concerto for Flute, Harp, and Orchestra in C Major, K. 299. Shifting to the higher flute (not an enviable task after living in Takemitsu’s guttural alto flute writing), Son brought crisp transparency to Mozart’s porcelain theme and variations, and Ramsay dazzling dexterity to the harp part’s music box-like tinkling. Niederhoffer proved his stylistic versatility with a balanced, unsentimental reading that would have served nicely as a flirtatious duet in one of Mozart’s comic operas.

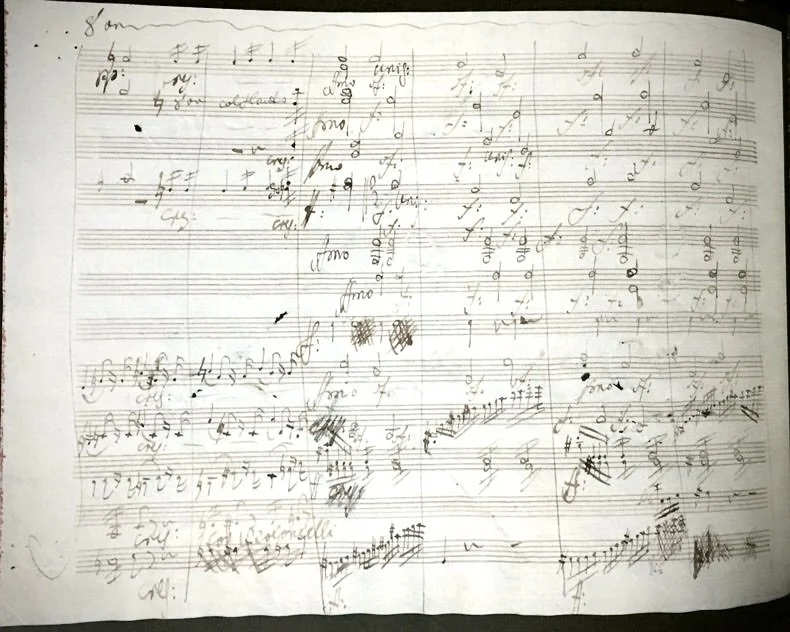

Béla Bartók’s night music is a trademark of his output — his usual vocabulary of Hungarian folk music extended by incorporating eerie sounds of the nocturnal world — such as in the Adagio third movement of Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, Sz. 106. This 1936 masterpiece was the concert’s main course (wisely not preceded by a mood-killing intermission, but merely a five minute pause), which Niederhoffer impressively conducted from memory, and placed in context as having been composed under the threatening encroachment of Fascism in prewar Hungary, as well as its later incorporation into the film soundtrack of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining.

Parlando nailed Bartók’s challenging score. Honoring the composer’s specific staging instructions, with the instruments positioned antiphonally, they delivered a riveting and dynamic performance, from a glassine ennui in the opening Andante tranquillo — obscure yet with great sense of line and expressive intention — to the driving and ratcheting rhythm of the angular Allegro. Percussion (including piano) was integrated organically into the strings ensemble, and the resulting organism listened and breathed together.

The mysterious Adagio conveyed a quiet terror with a portending xylophone solo and fraught timpani glissandi. Niederhoffer plotted the piece with the storytelling skill of a fine suspense writer, driving to the climax of the finale Allegro molto without giving away too much too soon, ensuring the denouement and emotional architecture of the work had maximum impact. The crashing final gesture jolted Merkin Hall as if waking from a nightmare — heart pounding, but relief that it was merely a dream — a testament to the power of music.