REVIEW: Phantasias and Variations - Angela Hewitt Turns Focus To Mozart

October 30, 2024

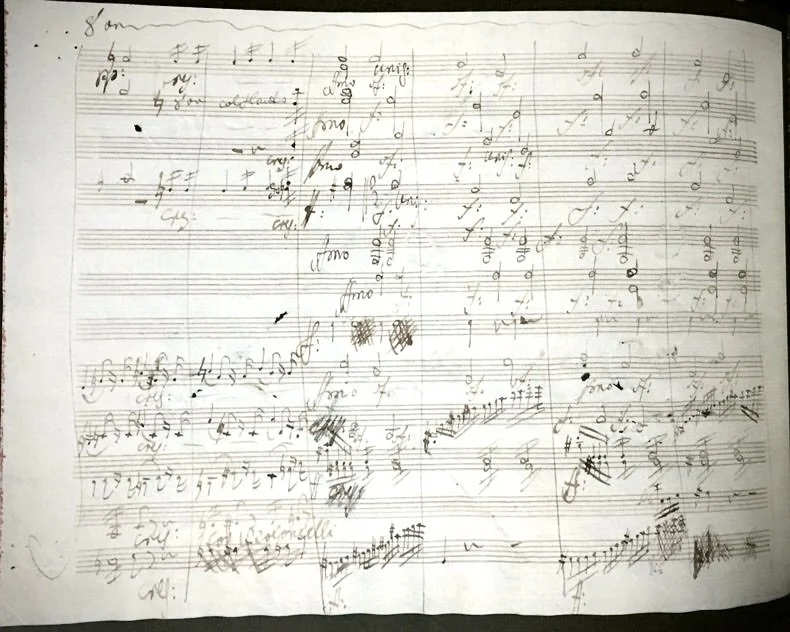

When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart completed his Fantasia in C Minor, K. 475, in May, 1785, he had recently settled in Vienna and married. He was at the peak of his career, a hot commodity in the big city. He had also recently made acquaintance with the music of Bach and Handel, which influenced and expanded his musical imagination. His skills as an improviser, creating “Phantasias” on the spot, were especially renowned, and this (along with the few cadenzas he notated) survive as the next best thing we’ll get to a recording of Mozart rhapsodizing at the keyboard.

The key of C minor has come to represent the key of pathos and drama. And the C minor Phantasia was published, together as Opus 11, as preludial companion to the composer’s only C minor piano sonata, Sonata in C Minor, K. 457, which he completed seven months earlier. Opus 11 was dedicated to — “composed for,” rather — Therese von Trattner.

The wife of Johann Thomas von Trattner, preeminent Viennese publisher forty years her senior, Therese was not only a wealthy pupil of the composer, but arranged for him to live in their house and hosted concerts of his music in their salon. What motivated Mozart to compose such powerful, emotional music for Therese, who would also go on to become godmother to his children? Trattner’s refusal to return Mozart’s letters to his wife, Constanze, upon his death is cause for speculation.

Angela Hewitt — esteemed as one of today’s master interpreters of J. S. Bach, having recorded and performed the Baroque master’s complete ouvre for ten fingers to great acclaim in recent years, has embarked on her next chapter, The Mozart Odyssey, a survey of Mozart’s piano concertos around the globe. Hewitt began her latest concert in Kaufman Auditorium at 92NY with Mozart’s Phantasia, beautifully paced and technically graceful, adding her own flare to the written ornaments — as an opera in miniature.

Photo © Keith Saunders.

Or at least the first act of an opera; this fantasia is more than just an introduction to the sonata, it’s several scenes in a hero’s journey. Hewitt imbued the opening Adagio — which begins in C minor, but immediately launches on a mysterious peregrination to distant lands, first coming to rest at B minor — with patience and readiness. B minor was an illusion; a simple yearning air in D major is interrupted by a storm, Allegro, and our hero is swept up and down the keyboard, diving, then taking taking flight, finally coming to rest in a scene out of an opera buffa, Andantino, in B-flat major. The plot thickens again, Piú Allegro, a struggle, Hewitt navigating the landing with wizard-like command until we return, wounded but alive, to C minor. Now, the murky motive in octaves communicates a lesson learned, and a shade of existential dread at the same time (in a fateful cadence that augurs Nicholas Britell’s indelible ‘Main Theme’ for HBO’s Succession).

Hewitt’s Mozart immersion came into fuller focus with the sonata, its Mannheim rocket immediately launching us to a dark place. Detailed finger-work, dispatched in broad gestures, provided space for the music’s rhetoric to speak. Hewitt follows through with her phrasing, the end of each phrase completing a thought. Laying the groundwork for the drama of Beethoven (whose C minor Pathétique waits in the wings), Hewitt balances the C minor sonata’s push and pull, its poetic tension, and packages it up in a plush sonic entity with orchestral planes of texture.

I usually prefer my Bach on an empty stomach, but Hewitt made a compelling case for capping the Mozart with Bach’s Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue in D Minor, BWV 903. Placing Mozart’s pianism in the larger context of musical and keyboard tradition, specifically in the balance between free-flowing improvisation and platonic form (song form, sonata form, fugue) — Apollo and Dionysus always holding sway — and Hewitt’s expertise was revelatory.

Following intermission, Hewitt preceded Johannes Brahms’ Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Handel, Op. 24, with G. F. Handel’s Chaconne in G Major, HWV 435. Brahms’ sizable opus — composed in 1861 as a birthday gift to Clara Schumann (more cause for speculation) — transforms an innocuous ditty into a towering edifice that eventually abstracts itself into a fugue. Adhering to Vladimir Horowitz’s famous adage that we should play Mozart like Chopin, and Chopin like Mozart, Hewitt played Handel like Brahms, and Brahms like Handel.

Handel’s 1733 fanciful variations on an upbeat tune foreshadowed the template for Brahms, traversing moods from melancholic to celebratory (sort of a shrunken Goldberg Variations) , and Hewitt fleshed out Handel’s Rococo textures with deep emotion and a Romantic sense of self-expression. Her Brahms, on the other hand, was crisply drawn; not an iota of counterpoint went unnoticed, and rarely has the composer’s sturdy classicism been more cleanly underlined. Each variation was like a visitation from one or another spirit of human nature — Tinker Bell on one shoulder, Jiminy Cricket on the other.

Hewitt’s fingers only seemed to tire in the bombast of the final variations, where you can also hear Brahms burning the midnight oil. The fugue, a numbing analysis of the atomic essence of the long-forgotten theme, built to an impressive peak of intensity, and a satisfying, full workout for Hewitt’s bright, bell-like Fazioli instrument. Hewitt’s inspired encore of Felix Mendelssohn’s first Song Without Words, was a soothing return to reality, like waking from a daze, a stupor — a phantasia.

***